Turandot poses three riddles. Three ministers warn of the death awaiting the candidate who does not answer them. And three artists then tried to complete Giacomo Puccini’s unfinished work as the dead composer intended. When Calàf, the dethroned Mongol prince who has fled to Peking, falls in love with Princess Turandot, he is in mortal danger. He can only be her bridegroom if he solves the Princess’s three riddles. Anyone who fails will be executed, like all the previous can didates. Calàf’s father, Timur, and Liù, who loves Calàf without his knowledge, plead with him in vain. He accepts the challenge.

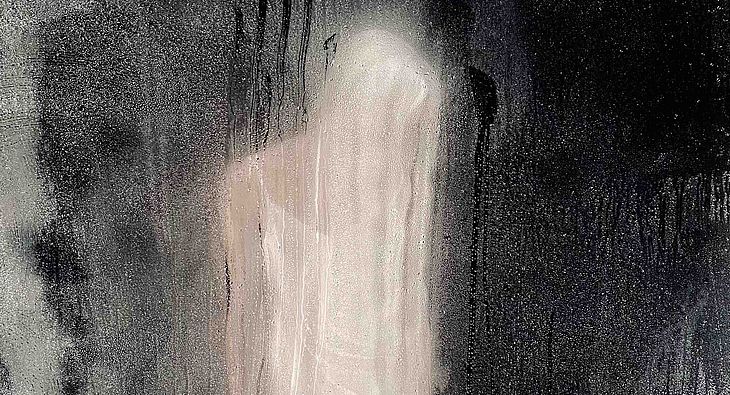

In the score of Puccini, the great musical storyteller, the individual and society form a highly disturbing contrast. The inflexible system which Turandot has created around herself has ceremonial and grotesque features, total organisation and manipulated mass hysteria. A world suspended between Turandot’s impregnable attraction and apparently unceasing rituals of application, warning, testing and death. It is peopled by shadows and priests. Harshly exaggerated ministers utter their warnings in a tone veering musically between provoca- tion and mockery – we believe them when they say they are equally pre- paring for a wedding and a funeral. As a basis for all this, the score and the state, there is the mob which varies between screaming for blood and begging for mercy for the con- demned. An incalculable, uncanny multitude.

Puccini coded his score with tonalities which his audience would ascribe to an oriental culture, a pentatonic musical language, and specific choice of percussion. These alien but famailiar sounds enact a play of deception. Embedded in Puccini’s own musical language, they create a new context, a Puccini Peking which seems to lead to distant regions, but in reality has no existence outside the theatre. Interestingly, Puccini’s Peking is related to his »Wild West« in La fanciulla del West, where the composer uses the pentatonic scale to hint at »foreignness«.

We can interpret the story as saying that Calàf has a similar feeling. He is fascinated by Turandot, and triumphantly solves her riddles. But even after he finds the last answer – »Turandot« – he is far from solving the nature of the princess. The fascination with strangeness – in this case, the princess – is a fascination with an illusion. Can Calàf succeed in reaching the woman behind it? Puccini’s composition ends with Liù’s death. He was unable to complete the grand finale, the happy encounter of Turandot and Calàf. But the composer left a hint, as well as an unfinished opera. He had sought a very special music, particularly for the final duet – the opera was meant to sound »tipica, vaga, insolita« at this point, according to Puccini’s annotation in the score. »Typical, indistinct, unusual.« He left himself a riddle with this, a task for his inheritors, specifically and generally. How do you set a story, an event, a feeling in music?

Upon the recommendation of the conductor of the premiere, Arturo Toscanini, Franco Alfano composed an ending. Independently of this, Toscanini ended the world premiere where Puccini’s composition finished, in memory of the composer. But Toscanini was not entirely satisfied with Alfano’s work, and polished and shortened it for the subsequent performances. This version initially established itself in the history of the piece, and Alfano’s ending was forgotten until its rediscovery in 1978. In 2002 Luciano Berio tried a new version of the final duet, with a particular focus on the kiss between Calàf and Turandot. All three versions have their separate perspective and appeal, although Franco Alfano's original ending most strongly portrays Turandot’s complex psy- chology. Claus Guth’s production is based on this original version.