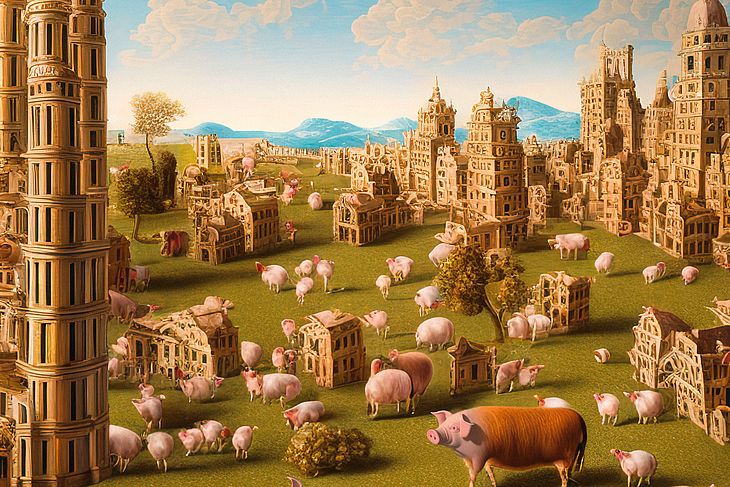

The audience will see the premiere of an opera based on Orwell’s classic of the dystopia of a failed liberation struggle. The animals on a squalid farm revolt against their tyrannical owners, but soon come under the rule of a new leader from their own ranks. »All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.« The first two translations appeared in Ukrainian and Polish in 1947, the year of the novel’s publication, a parable of the perversion of the Russian Revolution under Stalin’s dictatorship.

Naturally, they had to appear in western Europe. But for some time, it was by no means certain that you would find the English original in western bookshops, which met the manuscript with passive resistance. As Orwell noted in the foreword to the Ukrainian edition, his satire was not primarily aimed at the Soviet Union, which he knew only from periodicals and books, but at western illusions about the socialist wonderland in the east. These illusions implied the need to actively suppress and deny the totalitarian excesses of the regime, from the show trials and deportations through the genocides and the Terror Famine to the gulags.

The fact that a »left« author such as Orwell was writing against this uncritical admiration was met with silence and disinterest by circles regarding themselves as progressive. While at the time it was geopolitical and partypolitical interests (the Soviet Union as an ally in the struggle against Nazi Germany or capitalism) that buttressed the conspiracy of silence in western societies, it has mostrecently be eneconomic interests. The topical nature of Orwell’s dystopia is clear in view of the flagrant re-Stalinization of Russian society since the »oughts«. In the »post-factual« age of populism, the basic question of the book remains pressingly acute in the West. How can popular leaders use the stirring rhetoric of freedom and security while enforcing ruthless power and selfinterest?

Director Damiano Michieletto has long wished to bring Animal Farm to the opera stage. »The story is simple, a sort of fairy tale which, if you look at it more closely, deals with important issues such as power, oppression and propaganda in a nuanced way. The story is horrible but has comic elements as well. And it allows you to have not only a lot of solo roles but also a chorus«, Michieletto notes. He found the ideal partner in Alexander Raskatov. The composer was born to a Jewish Russian family in Moscow on the day of Stalin’s burial in 1953, not far from Red Square, and has won acclaim with his setting of another literary masterpiece critical of the Soviet Union – A Dog’s Heart, based on Bulgakov’s novella, and also premiered at Dutch National Opera, followed by performances in London, Milan and Lyon.

Raskatov worked closely with experienced librettist and dramaturge Ian Burton. It was important to him to connect Orwell’s external view of the Soviet empire with internal views, by incorporating original quotes by Stalin, Trotsky and secret service chief Beria, along with Beria’s acts of sexual violence. Raskatov shortened and condensed the text and pushed for the narrative to proceed in graphic situations, as far as possible. For his setting he developed a »scalpel style«, as he calls it, which contures events sharply and in high contrast. Raskatov also uses musical references to the history of his homeland. The score has no fewer than 21 solo roles, covering the full spectrum of human vocal ranges, where each one has a characteristic individual profile.

Director Michielletto set the story in an ab- attoir, rather than a farmyard. »The characters are waiting to be slaughtered here. They’re locked in cages, dreaming of freedom. To be an animal here means being a slave, meat, an object in the hands of humans.« Michieletto’s world premiere production was created as a Co-production of several commissioning houses. It had its premiere in Amsterdam on March 4, 2023; the Viennese premiere follows on February 28, 2024.